- Home

- Patricia Briggs

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Page 6

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Read online

Page 6

She stilled. She knew about villages, knew that most men’s fates were set in stone when they were little more than children and apprenticed to a trade—or else they were cast off never to be more than itinerant workers or soldiers. Women’s lives were dictated by their husbands.

Travelers were a little more free than that usually. A bowyer could decide to smith if he wanted to, as long as he continued to contribute to the clan. There were no guilds to restrict a person from doing as he willed. And women, women ran the clan. Only the lives of the Ordered were set out from the moment a Raven pronounced them gifted at birth.

No Traveler would ever have asked a Raven what she wanted to be.

The silence must have lasted too long because he said, “That question took me aback, today, too. But I learned something. What would you do?”

“Ravens don’t marry,” she said abruptly. He was easy to talk to, especially in the dark. “We can’t afford the distraction. We don’t do the normal chores of the clan. No cooking or firewood gathering. We don’t darn our own clothes or sew them.”

“You cook well,” he said.

“That’s because Ushireh couldn’t cook at all. I learned a lot when we were left on our own. But being a Raven’s not like being a baker, Tier. You could leave it and become a soldier. You can leave it now and become a farmer if you want. But I can’t leave being a Raven behind.”

“But if you could—what would you do?”

She leaned back on her hands and swung her feet back and forth, the bench being somewhat tall for her. In a dreamy, smiling voice she said, “I would be a wife, like the old harridan who runs an inn in Boarsdock on the western coast. She has a double handful of children, all of them taller than her, and they all cringe when she walks by. Her husband is an old sailing man with one leg. I don’t think I’ve ever heard him say anything but, ‘yes, dear.’ ”

She caught him by surprise and Tier gave a crack of laughter that he had to cover his mouth to suppress.

Smiling her satisfaction in the dark, she thought that the oddest thing about her statement was that it was the truth. That old woman ran her inn and her children and their wives and husbands and they all, every one of them, loved her. She lived in the daylight world, where shadow things wouldn’t dare show their faces and the children in her family had no more responsibility than grooming a few horses or cleaning a room could provide.

But the thing that Seraph envied the most was that one winter evening, when Seraph’s uncles entertained the boisterous crowd that gathered beneath the great fireplace and told them stories of haunts and shadow-things, that wise old woman shook her head with a laugh and said that she had better things to do than listen to tales of monsters fabricated to keep children up all night.

So it was that she stayed when she should have gone. But a week or a month would make little difference to her duties—a lifetime or two would make little difference as far as she could tell. So she stayed.

“Don’t pull that up. That’s an iris bulb, trimmed down now that it’s bloomed,” said Tier’s sister several weeks later. “Don’t you know how to weed?”

Seraph released the hapless plant unharmed, straightened, and almost groaned at the easing in her back. “No,” she said, though she’d told her as much when Alinath had set her to the task. How would she have learned to weed? The herbs and food plants she knew, but she’d no experience with flowers at all.

Tier had stormed off at lunch, beset by both his sister and his mother, who had gotten out of her bed only to try and push him into finding a wife. Since then Alinath had been picking at her as if it had been Seraph who’d sent Tier off to seek peace. Seraph had been set to half a dozen tasks, only to be sent to do something else because of some inadequacy in her work, real or imaginary.

“Well leave off then,” said Alinath. “Bandor or I will have to finish it, I suppose. You are utterly useless, girl. Cannot sew, cannot cook, cannot weed. The baking room floor needs cleaning—but mind how you do it. Don’t let the dust get into the flour bins.”

Seraph stood up and dusted off her skirt; she’d left off wearing her comfortable pants when she’d noticed that none of the Rederni women wore anything except skirts.

“It’s a shame,” she said finally. “That Tier, who wears courtesy as close as his skin, should have a sister with none at all.”

Before Alinath could do more than open her mouth, Seraph turned on her heel and entered the house through the baking room door. She regretted her comment as soon as she’d made it. The womenfolk in the clan were no more courteous in their requests than Alinath was. But they would have never turned their demands upon a Raven.

Moreover, Seraph knew the solsenti well enough to know that Alinath’s rudeness to a guest was a deliberate slight. Especially since, except for that first time, she was careful to soften her orders around Tier.

Seraph had done her best to ignore the older woman. She was a guest in Alinath’s home. She had no complaint with the work she was asked to do—which was no more work than anyone else did, except for Tier’s mother. And, by ignoring Alinath’s rudeness, Seraph bothered her more than any other response could have.

There was a more compelling reason to ignore Alinath’s trespasses.

Seraph let her fingernails sink into the wood of the broom handle as she swept with careful, slow strokes. A Raven could not afford to lose her temper. She took a deep, calming breath and sought for control.

The door opened and Alinath walked in. When she started to speak her voice was carefully polite.

“I have been rude,” she said. “I admit it. I believe that it is time for some plainer speech. My brother thinks you are a child.”

Seraph stared at her a moment, bewildered, her broom still in her hands. What did Tier’s opinion have to do with anything?

“But I know better,” continued Alinath. “I was married at your age.”

And I killed the ghouls who killed my teacher when I was ten, thought Seraph. A Raven is never a child. But she saw where Alinath was headed.

“I told Tier what you are up to, but he doesn’t see it,” said Alinath. “Anyone who marries my brother will have this bakery.”

Anyone who married your brother would be safe for the rest of their life, thought Seraph involuntarily, and envied his future wife with all of her heart.

“But you will never have him.”

Seraph shrugged. “And he will never have me.”

She went back to sweeping—and longing to be an old innkeeper who thought that ghouls and demons were stories told to frighten children. She crouched to get the broom under the low shelf of the table where Tier kneaded his bread.

“Where did you get those?”

Alinath lunged at Seraph. Startled, Seraph dropped the broom as Alinath’s hand clenched around Tier’s bead necklace; it must have slid out of her blouse when she crouched.

“Dirty Traveler thief!” shrieked Alinath, jerking wildly at the necklace. “Where did you get these?”

Seraph had heard all the epithets—but she’d been fighting her anger for weeks. The slight pain of the jerk Alinath gave the necklace was nothing to the outrage that Alinath had dared to grab her in the first place.

She heard the door to the public room open and heard Tier’s voice, but everything was secondary to the rage that swept through her. Rage fed by her clan’s death, Ushireh’s death, her desperate, despairing guilt at surviving when everyone else died, and lit by this stupid solsenti woman who pushed and pushed until Seraph would retreat no more.

Alinath must have seen some of it in her face because she dropped her hold on the necklace and took two steps back. The necklace fell back against Seraph’s neck like a kiss from a friend. Just before the wave of magic left her, the warmth of Tier’s gift allowed her to regain control. It saved Alinath’s life, and probably Seraph’s as well because magic loosed in anger was not choosy in its target.

Pottery shattered as the stone building shook with a hollow boom. Cooking spoons, wooden peels, and

baking tiles flew across the room. The great door that separated the hot ovens from the baking room pulled from its hinges and flew between Seraph and Alinath, hitting the opposite wall and sending plaster into the air in a thick white cloud as Alinath cried out in fear. Flour joined plaster as the door fell to the ground, taking two tables with it and knocking a barrel half-full of flour to its side.

Closing her eyes to the destruction and Alinath’s frightened face, Seraph fought to pull back the magic she’d loosed. It struggled in her grasp, fed by the anger that had engendered it. It made her pay for her lack of control, sweeping back to her call, back through her like shards of glass. But it came, and peelers and tiles settled gently to the floor.

Seraph opened her eyes to assess the damage. Alinath was fine—though obviously shaken, she had quit screaming as soon as she’d begun. The wall would have to be replastered and the door rehung, the jamb repaired or replaced. The jars of valuable mother, used to start the bread dough, had somehow escaped, and the number of broken pots was fewer than she’d thought. Neither Tier, nor the four or five people who had followed him into the room, had more damage than a coating of flour and plaster.

Shame cut Seraph almost as rawly as the magic had. It was the worst thing a Raven could do—loose magic in anger. That no one had been hurt, nothing irreplaceable broken, was a tribute to Tier’s gift and a little good luck rather than anything Seraph had done and so mitigated her crime not a whit. Seraph stood frozen in the middle of the baking room.

“I told you that she had a temper,” said Tier mildly.

“This was an ill way to repay your hospitality,” said Seraph. “I will get my things and leave.”

Tier cursed the impulse that had led him to invite the men he’d spent the afternoon singing with to try out an experimental batch of herb bread he’d been working on. That he’d opened the door to the baking room when he—and everyone else—heard Alinath cry out had been stupidity. He’d been warning his sister not to antagonize Seraph for the better part of a week.

“Mages aren’t tolerated here,” said someone behind him.

“She said she’d leave,” said Ciro. “She hurt no one.”

“We’ll leave in the morning,” said Tier.

“Strangers who come to Redern and work magic are condemned to death,” said Alinath in a tone of voice he’d never heard from her.

He looked at her. She should have appeared ridiculous, but the cold fear-driven anger on her face made her formidable despite the coating of white powder settling on her.

Someone gave a growl of agreement.

The ugly sound reminded Tier of the inn where he’d rescued her—or rescued the villagers from her. He realized that unless he managed to stop it, by morning his village might not be in any mood to let Seraph go.

An odd idea that had been floating in his head since he’d talked to Willon and then held Seraph in the wake of her night terrors crystalized.

“She is not a stranger,” lied Tier abruptly. “She is my wife.”

Silence descended in the room. Seraph looked at him sharply.

“No,” said Alinath. “I’ll not have it.”

She was in shock, he knew, or she’d never have said such a ridiculous thing.

“It is not for you to have or not have,” he reminded her, his voice gentle but firm.

“I won’t have her in this house,” Alinath said.

“We would have had to leave in any case,” said Bandor, who’d pushed through the crowd and into the baking room. He walked over to Alinath, and put his hand on her shoulder. “Once Tier had chosen his wife, whoever she was, we’d have had to leave. I’ve made some inquiries in Leheigh. The baker there told me he’d be willing to take on a journeyman.”

“There’s no need,” said Tier. Now that his choice was made, the words he needed to convince them all flowed easily. “There’s a place I intend to farm about an hour’s walk from here. I’ll have to get the Sept’s steward’s permission, which won’t be difficult to obtain since the land is not being used. There’s time to build a house before winter. We’ll live there, but I’ll work in the bakery through the spring when planting season comes. Then I’ll deed it to Alinath.”

“When were you married?” whispered Alinath.

“Last night,” lied Tier, holding out his hand to Seraph, who’d been watching him with an expression he couldn’t read.

She stepped to his side and took his hand. Her own was very cold.

“Yes,” said Karadoc, coming forward and putting a hand on Tier’s head as he used to when Tier was a boy. “There have been Rederni who were mages before. Seraph will harm no one.”

The crowd dispersed, and Bandor took Alinath to their room to talk, leaving only Karadoc, Tier, and Seraph.

“See that you come by the temple tonight,” said the priest. “I don’t like to keep a lie longer than necessary.”

Tier grinned at him and hugged the older man. “Thank you. We’ll stop by.”

When he left, Tier turned to Seraph. “You can stay here with me and be my wife. Karadoc will marry us tonight and no one will know the difference.” He waited, and when she said nothing, he said, “Or I can do as I promised. We can leave now and I’ll go with you to find your people.”

Her hand tightened on his then, as if she’d never let it go. She glanced once around the room and then lowered her eyes to the floor. “I’ll stay,” she whispered. “I’ll stay.”

PART TWO

CHAPTER 3

When Seraph reached the narrow bridge, the river was high and the wooden walkway was slick with cold water from the spring runoff. She glanced across the river and up the mountainside where Redern hung, terraced like some ancient giant’s stone garden. Even after twenty years, the sight still impressed her.

From where she stood, the new temple at the very top of the village rose like a falcon over its prey. The rich hues of new wood contrasted with the greys of the village, but, to her, that seemed to be merely an accent to the harmony of stone buildings and craggy mountain.

Seraph crossed the bridge, skirted the few people tending animals, and headed for the steps of the steep road that zigzagged its way up the mountain face, edged with stone buildings.

The bakery looked much as it had when she’d first seen it. The house was newer than its neighbors, having been rebuilt several generations earlier because of a fire. Tier had laughed and told her that his several times great-grandfather had tried to make the building appear old but had succeeded only in making it ugly. Not even the ceramic pots planted with roses could add much charm to the cold grey edifice, but the smell of fresh-baked bread wafting from the chimney gave the building an aura of welcome.

Seraph almost walked on—she could sell her goods elsewhere, but not without offending her sister-in-law. Perhaps Alinath would be out and she could deal with Bandor, who had never been anything but kind. Resolutely, she opened the bakery door.

“Seraph,” Tier’s sister greeted her without welcome from the wide, flour-covered wooden table where her clever hands wove dough into knots and set them on baking tiles to be taken back to the ovens for cooking.

Seraph smiled politely. “Jes found a honey-tree in the woods last week. Rinnie and I spent the last few days jarring it. I wondered if you would like to buy some jars to make sweet bread.”

Tier would have given it to his sister, but Seraph could not afford such generosity. Tier was late back from winter fur-trapping, and Jes needed boots.

Alinath sniffed. “That boy. If I’ve told Tier once, I’ve told him a thousand times, the way you let him wander the woods on his own—and him not quite right—it’s a wonder a bear or worse hasn’t gotten him.”

Seraph forced herself to smile politely. “Jes is as safe in the woods as you or I here in your shop. I have heard my husband tell you that as often as you complained to him.”

Alinath wiped off her hands. “Speaking of children, I have been meaning to talk to you about Rinnie.”

Seraph

waited.

“Bandor and I have no children, and most probably never will. We’d like to take Rinnie in and apprentice her.”

Seraph reminded herself sternly that Alinath meant no harm by her proposal. Even Travelers fostered children under certain circumstances, but it seemed to Seraph that the solsenti traded and sold their children like cattle.

Tier had tried to explain the advantages of the apprenticing system to her—the apprentice gained a trade, a means to make a fair living, and the master gained free help. In her travels, Seraph had seen too many places where children were treated worse than slaves; not that she thought Alinath would treat Rinnie badly.

So, Seraph was polite. “Rinnie is needed on the farm,” she said with diplomacy that Tier would have applauded.

“That farm will go to Lehr, sooner or later. Jes will be a burden upon it and upon Lehr for as long as he lives,” said Alinath. “Tier will not be able to give Rinnie a decent dowry and without that, with her mixed blood, no one will have her.”

Calm, Seraph told herself. “Jes more than carries his own weight,” she said with as much outward serenity as she could muster. “He is no burden. Any man who worries about Rinnie’s mixed blood is no one I want her marrying. In any case, she’s only ten years old, and marriage is something she won’t have to worry about for a long time.”

“You are being stupid,” said Alinath. “I have approached the Elders on the matter already. They know that scrap of land you have my brother trying to farm is so poor he has to spend the winter trapping so you have food on your table. It doesn’t really matter that you have no care for your daughter; when the Elders step in, you’ll have no choice.”

“Enough,” said Seraph, outrage lending unmistakable power to that one word. No one was taking her children from her. No one.

Alinath paled.

No magic, Tier’s voice cautioned her, none at all, Seraph. Not in Redern.

Seraph closed her eyes and took a deep breath, trying to cleanse herself of anger, and managed to continue speaking more normally. “You may talk to Tier when he returns. But if anyone comes to try and take my daughter before then…” She let the unspoken threat hang in the air.

Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane When Demons Walk

When Demons Walk Cry Wolf

Cry Wolf On the Prowl

On the Prowl Iron Kissed

Iron Kissed Hunting Ground

Hunting Ground Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly

Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly Burn Bright

Burn Bright Silver Borne

Silver Borne Storm Cursed

Storm Cursed Shifting Shadows

Shifting Shadows Frost Burned

Frost Burned River Marked

River Marked Silence Fallen

Silence Fallen Fair Game

Fair Game Moon Called

Moon Called Fire Touched

Fire Touched Dead Heat

Dead Heat Blood Bound

Blood Bound Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Night Broken

Night Broken The Hobs Bargain

The Hobs Bargain Ravens Shadow

Ravens Shadow Ravens Strike

Ravens Strike Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel)

Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel) Bone Crossed

Bone Crossed Dragon Blood

Dragon Blood Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12

Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12 Smoke Bitten

Smoke Bitten Steal the Dragon

Steal the Dragon 0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega)

0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega) Alpha and Omega

Alpha and Omega Raven's Strike rd-2

Raven's Strike rd-2![[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/mercy_03_-_iron_kissed_preview.jpg) [Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed

[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Raven's Shadow rd-1

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Frost Burned mt-7

Frost Burned mt-7 Dragon Bones h-1

Dragon Bones h-1 Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson

Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson Silver Borne mt-5

Silver Borne mt-5 Wolfsbane s-2

Wolfsbane s-2 Dragon Blood h-2

Dragon Blood h-2 Iron Kissed mt-3

Iron Kissed mt-3 Fair Game aao-3

Fair Game aao-3 Masques s-1

Masques s-1![[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/hurog_01_-_dragon_bones_preview.jpg) [Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones

[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Raven s Strike

Raven s Strike Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed

Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed Bone Crossed mt-4

Bone Crossed mt-4 Blood Bound mt-2

Blood Bound mt-2![[Mercy 01] - Moon Called Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/mercy_01_-_moon_called_preview.jpg) [Mercy 01] - Moon Called

[Mercy 01] - Moon Called River Marked mt-6

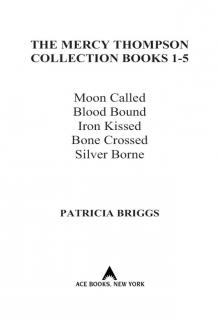

River Marked mt-6 The Mercy Thompson Collection

The Mercy Thompson Collection Moon Called mt-1

Moon Called mt-1 Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken

Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken