- Home

- Patricia Briggs

Smoke Bitten Page 3

Smoke Bitten Read online

Page 3

About three feet from the corner, on the side that ran the border between what had once been only my property and Adam’s, was a battered oak door—even though with very little effort anyone could have walked around the wall.

The wall and its door hadn’t been there when I came home from work, not an hour ago.

And I knew why Aiden had been so hot when he’d come into the kitchen. Underhill had made the wall, so she could have a door.

When Aiden had left Underhill, she’d missed him. After a misadventure in Underhill’s realm, we had made a bargain. A couple of times a month we escorted Aiden to the Walla Walla fae reservation, where there were many doors to the magical land.

Now there was a door to Underhill in our backyard.

At another time, I would have run back into the house. But the thought of all those hostile faces . . . of Adam’s hostile face was too much for me. My stomach churned and my heart hurt. Let Adam, Darryl, and Auriele deal with Underhill.

I hopped over the old barbed-wire fence, which continued where the stone wall left off, and strode through the field of sagebrush and dead cheatgrass toward my old house—or at least the house that stood where my old place had been.

A jackrabbit jumped out from somewhere, and my inner coyote took notice. There must have been something off about the rabbit for the coyote to be so excited by it when I wasn’t hungry at all.

I glanced at it again as it ran away. There was a ragged edge to the rhythm of its movement—not quite lame, just oddly awkward. But jacks are pretty fast, even sick ones, so it was out of sight before I could pin down what was wrong.

I stopped by the old VW Rabbit I’d originally placed just so to get back at Adam when he overstepped his bounds, back when we were nothing more to each other than neighbors. Adam was one of those people who walk around straightening paintings in museums. The old parts car with its various missing pieces had been nicely calculated to drive him crazy.

I thought about doing something else to it—but the Rabbit was part of the play-fighting that Adam and I did now. I wasn’t mad at Adam, wasn’t fighting with him—I would be mad tomorrow, maybe, when my heart didn’t ache. Today, I was just bewildered and sad. The old car couldn’t help me there, so I walked on.

I was pretty sure that Adam’s withdrawal from me had something to do with the witches, I reminded myself.

He’d seemed all right for the first few weeks after we killed all the witches. He’d had nightmares, but so had I.

I didn’t know when he’d decided to keep our mating bond closed because, to my shame, I didn’t notice at first.

I was bound to my mate, to my pack, and to a vampire. And if I thought about any of them too hard, I understood why animals caught in the jaws of iron traps sometimes gnawed their own limbs off to get free. Of the three bonds, the one with Adam bothered me the least. And when, a short time ago, it had been obstructed—I found out that I had become . . . completed by that bond.

Still, I had made very little effort to learn how it worked, leaving that to Adam. It was usually open only a little, just enough to let me know that Adam was okay and tell him the same about me. Sometimes he left it open wide—usually when we were making love, which was both amazing and overwhelming.

We weren’t living in each other’s heads, but I generally knew when he was having a good day—or a bad one, though only strong emotions made it through. I could tell where he was and if he was in pain or not. And he could tell the same about me. But his keeping it tightened down left us both some privacy. That way, he told me, I wouldn’t try to chew off my foot to get free.

Sometime after the witches, he had closed it tight and I hadn’t noticed until a few days ago. Once I noticed, then I could look back and realize it had been weeks since I’d felt much from our bond. The way it was now, I could not tell anything except that he was alive.

He had been working long hours—and so had I, my business freshly reopened and requiring more time than usual because of it. How little time we were spending together hadn’t seemed abnormal until I stopped to think about it. He had been spending a lot of hours at work, but he’d still had time to take care of pack business, and the problems of various pack members. But our time, the space he and I carved from our days and weeks, had disappeared.

I didn’t know when, exactly, it had happened or why, but I had been sure it was some kind of aftermath from the witches, from Elizaveta’s death. But tonight, his reaction, his willingness to believe I’d urge Jesse to change her plans without telling him, left me thinking that maybe the problem was me.

Was he finally tired of the trouble I caused? Or at least seemed to be surrounded by?

We hadn’t made love in weeks. My husband was a twice-a-night man unless one or the other of us was too beaten up. I found that with him, I was a twice-a-night woman, so it worked out well.

I leaned down to pat the old VW and then continued my walk. I didn’t want to think anymore, and movement seemed the right thing to do. I had no particular destination in mind other than away.

I stopped by the pole barn I had used as a secondary base of operations the whole time my garage was being rebuilt and glanced inside. It looked oddly empty, most of the tools moved back to the garage in town. The main occupant of the building was my old Vanagon.

I’d put a white tarp down and driven the van on top to see if I could find the leak in the coolant lines that ran from the radiator in the front of the van to the engine fourteen feet away. It was a last-ditch effort to find the leak before pulling all the lines and replacing them with new ones. I wasn’t hopeful, but I really wasn’t looking forward to taking the whole van apart.

I closed the door without checking the tarp and walked to the little manufactured home that had replaced my old trailer. The yard was in better condition than it had been when I’d lived there, Adam having installed an automatic watering system and added my house to his yard man’s routine.

The oak tree, a gift of an oakman, had escaped the fire that destroyed my old home. It had grown since I last paid attention to it, a lot more than it should have, I thought—though I was no gardener or botanist. Its trunk was wider around than both of my hands could span.

Impulsively, I put my tear-damp cheek against the cool bark and closed my eyes. I couldn’t sense it, but my head had to be quieter for me to listen to the subtle magic the tree held.

“Hey,” I told it. “I’m sorry I haven’t visited for a while.”

It didn’t respond, so after a moment I turned to the little manufactured house that I had never lived in. My old trailer had burned down and I’d moved in with Adam. Gabriel, Jesse’s ex-boyfriend who had been working for me when they met, had lived in it until he’d gone off to college. He’d planned to stay all summer, but a few weeks ago he’d moved his stuff out. At the time he’d told me that it didn’t make sense for him to take up space here when he was living in Seattle.

I’d known that there was something more, something that put sadness in his eyes, and I’d been pretty sure it had to do with Jesse by the way she didn’t come over to help him move. But I’d figured it was something that they would tell me when the time was right. So I hadn’t been surprised when Jesse had told me that she and Gabriel had broken up because she would not be joining him at school in Seattle.

I had Gabriel’s keys hanging on our key holder in the kitchen, and I wasn’t going back for them. The fake rock was still sitting next to the stairs—one side was blackened and melted a little and I could still smell the faint scent of the fire.

Adam had nearly killed himself trying to rescue me. I had not been in the house, but he’d thought I was. Even a werewolf can burn to death. Crouching beside the wooden steps, I remembered the burns that had covered him.

But I also remembered the look in his eyes today when he’d told me, if not in so many words, that he believed I would go behind his back on something t

hat I knew was important to him. That I would talk his daughter into an important life-changing decision without discussing it with him first.

I closed my hand on the plastic rock and found a shiny new key. Gabriel had put his spare key the same place I had. Adam, who ran a security company, would have chided us both had he known.

I opened the door.

Gabriel had cleaned the house before he left—and then his mother and sisters came and cleaned it again. She explained to me, “Gabriel is a good boy. But no man ever cleaned a house as well as a woman.”

And with that sexist statement, she proceeded to prove her point. The house smelled clean, not musty as do most places that are left empty for very long. The carpet looked new; the vinyl in the kitchen and bathrooms were pristine.

There was a white envelope on the counter of the kitchen marked Jesse in Gabriel’s handwriting. I left it alone. Someone had already opened Jesse’s mail today—I wasn’t going to do that again.

The manufactured house was larger than my old trailer had been, and better insulated, too. Even though the day had been hot and the electricity was off, the house was a bearable temperature.

Walking through the empty, clean house wasn’t making me feel any better. I was starting to think that I’d abandoned the fight in the middle—which wasn’t like me at all. I stared out the window of the master bedroom over at my home. My real home.

Time to go back and fight for it, I decided.

I strode out of the bedroom—and there was a woman standing in the living room with her back to me. Her hair was long and blond and straight. She wore a navy A-line skirt and a white blouse.

“Excuse me?” I said, even as I was wondering how she’d gotten into the house without me noticing her at all. I could smell her now, a light fragrance that was familiar.

She turned to look at me. Her face was oddly familiar, too. Her features were strong—handsome rather than lovely. A face made for a character actor. I’d have said “memorable,” but I couldn’t remember where I’d seen her before. Her eyes were blue-gray.

“I don’t understand,” she said. “He loves me. Why would he do such a thing?”

And upon her words, blood began to flow from wounds that opened on her body—shoulder, breast, belly, one arm, and then the other—and the smell of fresh blood permeated the house.

2

It was her voice that I recognized. My old neighbor, Anna Cather. I’d seen her just the day before yesterday at the gas station. The reason I hadn’t known her immediately was that the Anna I knew was in her seventies. The woman who stared at me while her blood pooled on the gray carpet, turning it black at her feet, was in her twenties.

Ghosts were like that.

I felt a rush of grief and though I knew better—of all people, I knew better—I hurried to her side and reached out to her. Her shoulder under my hand was as solid as any living person’s would have been, solid and cold as ice. Much colder than an actual corpse’s would have been.

She was dead, my happy neighbor who liked to eat my cookies and bring me bouquets of flowers from her garden.

Seeing ghosts was the other thing I did besides turn into a coyote. I knew that merely by paying attention to her, I made the ghost more real, gave her power. Gave it power—though I hesitated a lot more when I said “it” around ghosts than I used to. I was no longer convinced that all ghosts were nothing more than the shed remnants of the people they had been—things without feelings or thoughts. What exactly they were, I wasn’t sure, but I was doubtful that anyone else knew, either.

That I had noticed her was bad, but touching her was worse. If I didn’t want her shade haunting this house for years to come, I needed to walk away. But Anna was—had been—my friend.

So instead of turning my back on her, I left my hand where it was. “Anna, what happened?”

Tears slid down her face as blood started to trickle out of the corner of her mouth. She raised her hands to cover her mouth, then hugged herself with those bloody hands, hunching slightly as if her stomach hurt. She looked at me with horror-filled eyes.

“Why?” she asked me, sounding bewildered. “Why did he do it? He is the gentlest soul—you know how he is. He even takes spiders outside instead of killing them.”

“And live traps the mice,” I said in disbelief. “Anna, are you saying that Dennis killed you?”

Dennis, Anna’s husband, loved her with all of his gentle soul. They didn’t have a perfect marriage. I knew she took once-a-year vacations on her own, and that after his retirement left him following her around like a devoted dog just waiting for the next thing requested of him, she’d started volunteering at hospitals, animal shelters, and anywhere else that would get her out of the house. But she loved him, and he loved her—so they worked it out.

She hunched over and looked at me. “Why?” she said again. “Why did he do it? He is the gentlest soul—you know how he is. He even takes spiders outside instead of killing them.”

She wasn’t talking to me; she was on repeat.

Ghosts sometimes interacted with me as if they were still the person whose shade they were. But only sometimes. Sometimes they were locked into a particular moment, or sequence of moments. That Anna had repeated herself so exactly indicated that she was one of those. She had no answers to give me.

“Anna,” I said, knowing nothing I said could possibly make any difference. “I am so sorry.”

The wounds on her body might have been analogous to actual wounds—in which case someone (Dennis didn’t feel possible, despite what she had indicated) had attacked and stabbed her. But ghosts were not tied to physical reality. The wounds could represent what she felt when she died, or how she felt about death.

A 9mm gun spoke, breaking the normal early-evening sounds of light traffic, birdsong, and dogs barking. Anna and I both turned to look toward her house, though repeaters don’t usually notice things outside their narrow reality.

The sound of the gun left me with a heavy certainty in my chest, though gunfire in this rural neighborhood wasn’t uncommon. I felt sick. Anna’s face lit with a relieved smile.

“Oh,” she said. “Dennis?”

The blood disappeared from the carpet and from her body. The dark stains faded from existence between one breath and the next as if they never had been—because in some ways they had not. Only the tears on her cheeks and the lingering scent of fresh blood remained.

“Dennis?” she asked a second time, but this time her voice sounded like someone who hears a door open and is fairly sure of who has come in.

Her body softened with happiness. I stepped away, letting my hands fall from her. She took a step forward, not toward me, but toward something I couldn’t see. She lifted both of her hands, her whole body leaning to rest upon . . . Dennis, I supposed.

“My love,” she said, looking up—Dennis had been a great deal taller than she.

And I was alone again in the living room.

* * *

• • •

Wasting no time, I ran to the Cathers’ house. In the short time I’d been inside, dusk had turned to night. The darkness didn’t bother me—I can see as well in the dark as any coyote. It did provide me cover so no one would notice that when I ran full speed, I was faster than I should have been. The Cathers had been my closest neighbors, other than Adam, but they were still nearly a quarter of a mile away.

No one else seemed to have been disturbed by the sound of the gun going off. But no one else had had Anna’s ghost in their living room, either.

When I reached Anna and Dennis’s yard, caution made me stop to get a good look around. Someone had shot a gun over here, and though I had my suspicions of what had happened, I couldn’t be absolutely certain. There might still be an active shooter.

Dennis’s gray Toyota truck was parked next to Anna’s silver Jaguar in the carport. Everything was neat and tidy

except . . . I stopped by one of the big raised garden beds that Dennis had built for Anna. On one of the timbers that edged the beds was a box with a new sprinkler head. I could see that someone had been digging a hole—presumably to fix a sprinkler—but hadn’t gotten far.

Dread in my heart, I climbed up the steps to the front door. The Cathers’ house, like many in Finley, was a manufactured house—a much larger and grander version than the one I’d just left. Painted tastefully in gray and white, the house suited the Cathers, being neat and tidy. The only extravagance was the graceful wraparound porch.

I was wondering if I should wait for the police—and that meant I had to call them first—rather than open the door. If I just went in, I might ruin evidence. But if I waited for the police, they would go in first and mess up the scent markers that might allow me to figure out what had happened.

The front door, I noticed, was slightly ajar.

Trying to be as unobtrusive as possible, I pushed the door open with my foot, but it only opened about ten inches—stopped by a jean-covered leg on the tile floor. The smell of death washed over me—Dennis, and then a few seconds later I could smell Anna.

I’d been almost certain that Dennis was dead when I’d heard the gunshot. Closer to certain at Anna’s last words. I hadn’t realized how much I’d hoped I was wrong until I opened their door and found the body.

Faced with the reality that both Dennis and Anna were dead, I found that I was not very concerned with fingerprints and pristine crime scenes anymore. I slid through the narrow opening between the door and the frame, stepping over Dennis’s leg and into the Cathers’ living room.

Dennis’s body lay crumpled midaction, as if he’d been walking toward the door when he’d shot himself. He had shot himself. The trigger finger of his right hand was still caught in the trigger guard. He’d done it right—put the gun in his mouth and blown out the back of his head.

Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane When Demons Walk

When Demons Walk Cry Wolf

Cry Wolf On the Prowl

On the Prowl Iron Kissed

Iron Kissed Hunting Ground

Hunting Ground Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly

Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly Burn Bright

Burn Bright Silver Borne

Silver Borne Storm Cursed

Storm Cursed Shifting Shadows

Shifting Shadows Frost Burned

Frost Burned River Marked

River Marked Silence Fallen

Silence Fallen Fair Game

Fair Game Moon Called

Moon Called Fire Touched

Fire Touched Dead Heat

Dead Heat Blood Bound

Blood Bound Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Night Broken

Night Broken The Hobs Bargain

The Hobs Bargain Ravens Shadow

Ravens Shadow Ravens Strike

Ravens Strike Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel)

Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel) Bone Crossed

Bone Crossed Dragon Blood

Dragon Blood Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12

Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12 Smoke Bitten

Smoke Bitten Steal the Dragon

Steal the Dragon 0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega)

0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega) Alpha and Omega

Alpha and Omega Raven's Strike rd-2

Raven's Strike rd-2![[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/mercy_03_-_iron_kissed_preview.jpg) [Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed

[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Raven's Shadow rd-1

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Frost Burned mt-7

Frost Burned mt-7 Dragon Bones h-1

Dragon Bones h-1 Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson

Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson Silver Borne mt-5

Silver Borne mt-5 Wolfsbane s-2

Wolfsbane s-2 Dragon Blood h-2

Dragon Blood h-2 Iron Kissed mt-3

Iron Kissed mt-3 Fair Game aao-3

Fair Game aao-3 Masques s-1

Masques s-1![[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/hurog_01_-_dragon_bones_preview.jpg) [Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones

[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Raven s Strike

Raven s Strike Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed

Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed Bone Crossed mt-4

Bone Crossed mt-4 Blood Bound mt-2

Blood Bound mt-2![[Mercy 01] - Moon Called Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/mercy_01_-_moon_called_preview.jpg) [Mercy 01] - Moon Called

[Mercy 01] - Moon Called River Marked mt-6

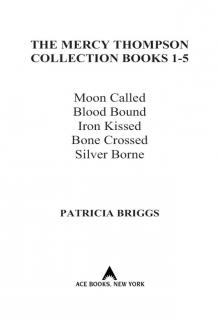

River Marked mt-6 The Mercy Thompson Collection

The Mercy Thompson Collection Moon Called mt-1

Moon Called mt-1 Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken

Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken