- Home

- Patricia Briggs

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Page 15

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Read online

Page 15

“No one knows about the forest king,” said Lehr, turning over the last spade of dirt. “But Hennea said that whoever sent the letter to the priest knew what we are.”

“Yes,” agreed Seraph. “How did they know, not only that I am Raven, but exactly what my skills are? Most Ravens cannot read the past in an object. These men knew what trail Tier would take home—and it’s not the way he left.”

Lehr frowned. “Not even I knew what path Papa takes home. He kept it quiet because the furs are worth a lot of money—did you notice that there is no trace of the furs? They would have been packed over Frost’s hindquarters, which weren’t even scorched.”

“No, I hadn’t noticed,” said Seraph. “So thrifty of them.”

Lehr packed in a layer of dirt with his foot. “I suppose that someone could have overheard Jes talking about the forest king—but Jes seldom talks to anyone but the family. No one else really pays attention to what he says anyway. And if none of us knew what magic you could do until Forder brought back Frost’s bridle, who would know what you could do?”

She waited, watching him think about it. If he came up with the same answer as she did…

“Bandor used to hunt with Papa, didn’t he?” Lehr whispered it. “During the first years when the bakery used to have to support the farm, too? Jes was just a baby.”

“That’s right,” Seraph said.

“And, after you and Papa got married, Bandor was the only one who used to talk to you. He knows a lot about the Travelers—did you tell him what kinds of things you could do?”

“Yes,” she said.

“And Bandor knows about Jes’s stories of the forest king—but he doesn’t believe them, Mother.”

She smiled at him grimly. “Do you know who your father thinks the forest king is? I mean aside from Jes’s dealings with him?”

“No.”

“What if I told you that in a very old language, ell means king or lord and vanail is forest. If you put them together—”

“Ellevanal?”

Seraph had never seen anyone’s jaw drop before; it was an unattractive expression.

“Do you mean,” whispered her son, “that Ellevanal, god of the forest and growing things, the Ellevanal, Karadoc’s Ellevanal, is Jes’s forest king?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Today is the first time I’ve met him, and I didn’t ask. He doesn’t look like a god, does he? But I know that Tier was convinced of it, and he told your Aunt Alinath what he thought.”

Alinath had been at her worst, telling Tier that Seraph couldn’t give Jes the kind of attention that he needed. That Seraph encouraged Jes’s problems by listening to his stories about his made-up friend. A boy, she’d said, needed to understand that lying was not acceptable. She hadn’t liked it when Tier suggested Jes hadn’t lied at all.

Seraph smiled grimly. “Bandor was there when he said it.”

But Lehr was still worried about other matters. “But the forest lord belongs here, to our forest. Ellevanal is worshiped everywhere—I mean, Karadoc has had apprentices, and there’s a larger church in Korhadan.”

“I don’t worship gods,” said Seraph. “You’ll have to take it up with the forest king next time you meet him.”

Lehr thought about her answer, but it seemed to satisfy him because he changed the subject. “Uncle Bandor loves us, loved… loves Papa. He wouldn’t do anything to hurt Papa.”

“So I believe,” agreed Seraph. “But you and I both came up with his name. He’s become one of Volis’s followers. I think that we need to be cautious around him until we know more.”

“So what are we going to do now?”

“First we’ll finish here, then I have a few questions for the priest. Can you take us by the quickest route to Redern?”

“Yes,” he said. “But we won’t make it before dark.”

“No matter,” Seraph said coldly. “I don’t mind waking up a few people.”

Or tearing them limb from limb if she had to. Tier had been taken, alive—because she couldn’t bear it otherwise—and she intended to find out where he was. And tearing someone limb from limb sounded very, very good. Let Volis face a Raven who knew what he was when he didn’t have a cadre of wizards to protect him. Oh, she would have her answers from him before she slept this night.

“What about Rinnie?” asked Lehr.

“Jes will have gotten back from taking Hennea to the village by now. Rinnie will be safe with him.”

Gura barked, and Rinnie looked up from her gardening. But whoever had disturbed the dog was on the other side of the house.

Rinnie jumped to her feet and dusted off her skirt. She put her hand on Gura’s collar and set off to see who had come.

CHAPTER 7

He opened his eyes to utter darkness and a cold stone floor under his cheek, though he didn’t remember going to sleep. He took a deep, shaken breath and tried to determine how he got here, wherever here was. The last thing Tier remembered was riding Frost down the mountain on the way back home.

Undeniably, he was no longer on the mountain. The stone floor beneath his hands was level, and his fingers found the marks of a chisel. He was in a room, though he could hear water flowing nearby.

He rose cautiously to hands and knees and felt his way forward until his hands closed on grating set into the floor, the source of the sound of water. The bars were too close to let him put anything wider than his finger through and the water flowed well below that. He tried to pull up the grate, but it didn’t so much as shift.

Hours later he was hungry, thirsty, and knew that he was in a room six paces wide by four paces long. An ironbound wooden door was inset flat against one of the narrow walls with the hinges on the outside.

The stonemason responsible for the walls had been very good, leaving only the smallest of fingerholds. Tier’d fallen three times, but he finally climbed the corner of the room until he touched a wooden ceiling. By his reckoning it was about twice his height to the floor. With a foot braced on adjacent walls he couldn’t put any significant pressure against any of the boards, though he tried all the ones he could reach from his perch.

At last he climbed back down, convinced that the room he was in wasn’t anywhere in Redern—or Leheigh either for that matter. He’d been inside the Sept’s keep a time or two, and the walls in this room—which had obviously been designed as a prison cell—were better formed than the walls of the great hall in the Sept’s keep.

Why had someone gone to the trouble of hauling him off the mountain and imprisoning him? It wasn’t as if he, himself, would be worth money to anyone, not the kind of money that would be important to anyone who could afford a cell built like this one was.

He had a long time to think about it.

Emperor Phoran the Twenty-Seventh (Twenty-Sixth if he didn’t count the Phoran who united the Empire—it was the first Phoran’s son who had declared himself emperor) stretched his feet out before him and cast a practiced leer at the woman sitting on him. She was all but baring her breasts at him, the stupid cow. Did she really think that his favors were likely to be won by such as she?

He snagged a mug from a nearby serving tray and drank deeply, closing his eyes to the party that had somehow spread from the dining hall to his own private rooms. The laughter of a nearby woman cut through his spine with its falseness.

He wondered what his so-long-ago ancestor would have thought about such decadence. Would he still have set aside his plow to organize his fellow farmers into a militia to defend themselves against bandits? Or would he have turned back to his farming, ashamed that his loins could breed such a degenerate creature as the current emperor?

Phoran sighed.

“Am I boring you, my love?” asked the woman on his lap archly.

He opened his mouth to inflict the kind of cruel remark that had become second nature to him over the past few years, but instead he sighed again. She wasn’t worth it—dumb as a sheep and oblivious to fine nuances of language.

&nb

sp; Instead he pushed her off and away with a pat. “Go find someone else to cuddle tonight, there’s a love. This fine ale suits me better than a woman… tonight.”

Someone giggled as if his remark had been witty. The woman who’d been on his lap swayed her hips and half staggered onto the lap of a handsome young man who’d been seated on the end of the bed, watching the party with a jaundiced eye—Toarsen, Avar’s younger brother, who’d doubtless been told to watch over Phoran while Avar was out in the wilds taking stock of his new inheritance.

Phoran swallowed the better part of the contents of his cup then closed his eyes once more. This time he left them closed. Maybe if he feigned a drunken stupor (a common enough occurrence) they would all go away.

He let his hand fall away from his lips and the mug fell on the plush rug his great-grandfather had imported from somewhere at great expense. He hoped the dark ale ruined the rug. Then the chatelaine would run to Avar when he returned. Avar would listen gravely, and when the chatelaine left, he would laugh and pat Phoran on the back—and pay attention to him again.

Avar, mentor, best friend, and Sept of Leheigh now that his miserly old father had died hadn’t had much time to spend with his emperor lately. Spitefully, Phoran wondered if he should take away the title and lands that kept Avar from noticing that his emperor needed a friend more than he needed another Sept.

Tears of self-pity welled up and were firmly repressed. Tears were something he shed alone, never, never in front of the court no matter how drunk he was.

Self-indulgence aside, Phoran had no intention of taking Avar’s inheritance away. He even knew that Avar had to attend to his duties; he just wished he had duties to attend to as well. The endless parties had become… sickening—like too much apple mead. When would he be old enough to start ruling his empire?

Someone patted his cheek and he slapped at the hand, purposefully making the movement clumsier than necessary. He could drink a fair bit more than he had tonight before it affected him much.

“He’s unconscious.” Phoran recognized the voice. It was Toarsen. He must have gotten rid of the cow, too. “Let’s get this room cleared out.”

The Emperor listened while people shuffled away. At last the guardsmen came in to gather the few who’d passed out in the chamber. His door shut behind them and he was alone. Without people around, without Avar to keep it at bay, the Memory would come for him, again.

Before he could sit up and call them back, someone spoke. It startled him so that for a moment he didn’t quite recognize the speaker.

“Some emperor,” sneered a voice quite close to his ear. Not his Memory but someone who’d stayed after the guardsmen had left—Kissel, the younger son of the Sept of Seal Hold. The relief of his mistake almost blinded Phoran to the words. “A beardless boy who drinks himself to sleep every night.”

“Got to hand it to Avar,” agreed Toarsen. “I thought that the boy would be harder to tame and we’d have to have him killed like the Regent was. But Avar’s turned him into a proper sot who jumps when Avar asks.”

“Well I’d rather not have to be on the cleanup committee. He’s gone to fat like a capon. Come help me heave him to the bed.”

They managed it with grunts and swearing while Phoran concentrated on being as heavy as possible. How dare they speak of him like this? He’d fix these imbeciles. Tomorrow his guards would have their heads. He was emperor, they’d forgotten that. He’d have Avar… Avar was his friend. Just because Avar’s brother talked that way about him didn’t mean that Avar felt the same way. Avar liked him, was proud of the way he could outdrink and outinsult any man in the court.

“And why isn’t Avar here to do the honors?” asked Kissel. “I thought he was going to see the Emperor tonight after resting yesterday.”

Avar was in Taela?

“He had some pressing business,” grunted Toarsen, pushing Phoran toward the center of the bed. “He’ll admit to coming in late tonight and greet the Emperor over breakfast.”

When the men left him alone in his room, the Emperor opened his eyes and rolled off the bed. He walked to the full-length mirror and stared at himself by the light of the few candles that had been left burning.

Mud-colored, too-fine hair that had been coaxed into ringlets this afternoon hung limply around his rounded face, spotty and pale. Hands that had once had sword calluses were soft and pudgy, covered with rings his uncle had eschewed.

“Ruins your sword grip, boy,” the regent had said. “A man who can’t protect himself depends upon others, too much.”

Phoran touched the mirror lightly. “But you died anyway, Uncle. You left me alone.”

Alone. Fear curled in his stomach. Unless Avar was with him, the Memory came every night.

If Avar was in Taela, as Toarsen had claimed, he’d be staying with his mistress in the town. Phoran could send a messenger to bring him here.

The Emperor stared at his image in the mirror and rolled up the sleeve of the loose shirt he wore. In the reflection the faint marks the Memory left on him each night were almost invisible in the dim candlelight.

Avar planned to lie to his emperor: Avar, who was Phoran’s only friend.

The Emperor made no move to summon a messenger.

Food came at irregular intervals through a small opening near the floor that Tier had somehow missed on his first, blind, inspection of the cell. An anonymous hand opened the metal covering and shoved a tray of water and bread through, shutting and latching the cover before Tier’s eyes even adjusted to the light.

Still, he’d grown grateful for those brief moments, for the reassurance that he was not blind.

The bread was always good, flavored with salt and herbs and made with sifted wheat flour rather than the cheaper rye. Bread fit for a lord’s table, not a prison cell.

First he’d tried to fit his situation into some logical path, but nothing about his captivity made sense. Finally he’d come to the conclusion that he was lacking some information necessary for a solution.

Only then had he raged.

He’d slept when he was tired, worn-out from anger and fruitless attempts to find a way out of the cell. When he’d realized that he was losing track of time he told himself stories, the ones he’d gathered from the old people of Redern, saved word for word from one generation to the next. Some of those were songs as well as stories, ballads that took almost an hour each to sing.

When the toll of the hours grew too great, he’d quit singing, quit thinking, quit raging, and given in to despair. But even that left him alone eventually.

Finally, he developed habits to fill the empty hours. He did the exercises he’d learned when he’d been a soldier. When he ran out of the ones he could do in his confined space, he made up others. Only after he was sweating and panting, he’d sit down and tell one story. Then he’d either rest or exercise again as the impulse took him.

But it was the magic that had given him purpose.

He’d known some of the things his magic could do. Seraph had told him what she knew—and, despite the danger, he’d used it some over the years. It helped that his magic wasn’t the showy sort that people all knew about, like Seraph’s. His magic was more subtle.

He could calm an angry drunk or give a frightened man courage with his songs. Such things as any music could do, but with more effect. When he chose, he could commit a song or letter to memory and recall it, word perfect, years later. When he’d sung at the tavern in Redern, he almost always gave his last song a push to cheer his audience.

It had made him feel guilty, because Seraph had given up her magic entirely. But she’d never seemed to mind, never seemed to miss the power that she’d set aside.

He could never have set aside his music.

There were some things he’d avoided. Some things were harmful to his audience; music alone shared the darker emotions with his audience, never magic. He was very careful not to use his magic to persuade others to his will—words were enough. And then there were the thin

gs too obviously magic to use in Redern.

Alone in the darkness of his cell, he’d succeeded in creating small lights to accompany his songs the first time he tried. They were flickering, faint things, but they comforted him.

Sounds were more difficult, even though he’d accidently called them once before. After a particularly nasty battle, he and a bunch of the other officers got roaring drunk and someone thrust a small lyre, part of the spoils, into his hands. The song he’d sung had included fair maidens and barnyard animals. He was pretty certain he’d been the only one who noticed that the moos and quacks of the chorus were accompanied by the real thing.

He had been trying to re-create the experiment the first time his visitor arrived.

The constant dark had honed his other senses, and the scuff of a foot on the boards above him stopped him midword. He’d sat silently, waiting for something more.

Finally, barely audible over the burble of the water that flowed under the grating in the back corner of his cell, he’d heard it again.

It hadn’t been a rat; a rat was too light to make a stout board creak under its weight. He’d been almost certain that the noise was made by a person.

“Hello,” he’d said. “Who is there?”

The boards had given a small, surprised squeak and then there was nothing. Whoever it had been, he had left.

Some unknowable span of time later, while Tier was doing push-ups, he’d heard it again. He’d stilled, too worried that he would drive whoever it was off again if he made another move. He hadn’t heard another sound, but somehow he knew that his visitor was gone. Desperate for company, Tier turned his thoughts toward enticing his visitor to stay.

Tier awoke with the knowledge that there was someone nearby. He hadn’t heard anything, but he could feel that someone stood above him listening. He sat up, leaned his back against the wall, and began his story with the traditional words.

“It happened like this,” he said.

If he pretended that his eyes were closed, he could think himself leaning against the wall at home telling stories to his own restless children so they’d fall asleep faster. Seraph would be cleaning—she was always in motion. Maybe, he thought, she would be grumpy as she sometimes got when Rinnie was tired and the boys were restless. Her face would be serene, but the tautness of her shoulders gave her away.

Wolfsbane

Wolfsbane When Demons Walk

When Demons Walk Cry Wolf

Cry Wolf On the Prowl

On the Prowl Iron Kissed

Iron Kissed Hunting Ground

Hunting Ground Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly

Patricia Briggs Mercy Thompson: Hopcross Jilly Burn Bright

Burn Bright Silver Borne

Silver Borne Storm Cursed

Storm Cursed Shifting Shadows

Shifting Shadows Frost Burned

Frost Burned River Marked

River Marked Silence Fallen

Silence Fallen Fair Game

Fair Game Moon Called

Moon Called Fire Touched

Fire Touched Dead Heat

Dead Heat Blood Bound

Blood Bound Dragon Bones

Dragon Bones Night Broken

Night Broken The Hobs Bargain

The Hobs Bargain Ravens Shadow

Ravens Shadow Ravens Strike

Ravens Strike Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel)

Storm Cursed (A Mercy Thompson Novel) Bone Crossed

Bone Crossed Dragon Blood

Dragon Blood Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12

Smoke Bitten: Mercy Thompson: Book 12 Smoke Bitten

Smoke Bitten Steal the Dragon

Steal the Dragon 0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega)

0.5 On The Prowl (alpha and omega) Alpha and Omega

Alpha and Omega Raven's Strike rd-2

Raven's Strike rd-2![[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/24/mercy_03_-_iron_kissed_preview.jpg) [Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed

[Mercy 03] - Iron Kissed Raven's Shadow rd-1

Raven's Shadow rd-1 Frost Burned mt-7

Frost Burned mt-7 Dragon Bones h-1

Dragon Bones h-1 Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson

Shifting Shadows: Stories from the World of Mercy Thompson Silver Borne mt-5

Silver Borne mt-5 Wolfsbane s-2

Wolfsbane s-2 Dragon Blood h-2

Dragon Blood h-2 Iron Kissed mt-3

Iron Kissed mt-3 Fair Game aao-3

Fair Game aao-3 Masques s-1

Masques s-1![[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/03/hurog_01_-_dragon_bones_preview.jpg) [Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones

[Hurog 01] - Dragon Bones Raven s Strike

Raven s Strike Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed

Mercedes Thompson 03: Iron Kissed Bone Crossed mt-4

Bone Crossed mt-4 Blood Bound mt-2

Blood Bound mt-2![[Mercy 01] - Moon Called Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/09/mercy_01_-_moon_called_preview.jpg) [Mercy 01] - Moon Called

[Mercy 01] - Moon Called River Marked mt-6

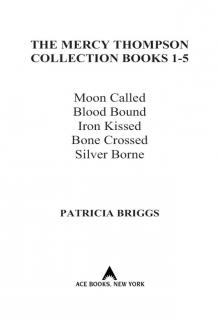

River Marked mt-6 The Mercy Thompson Collection

The Mercy Thompson Collection Moon Called mt-1

Moon Called mt-1 Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken

Mercy Thompson 8: Night Broken